Via Momentum.

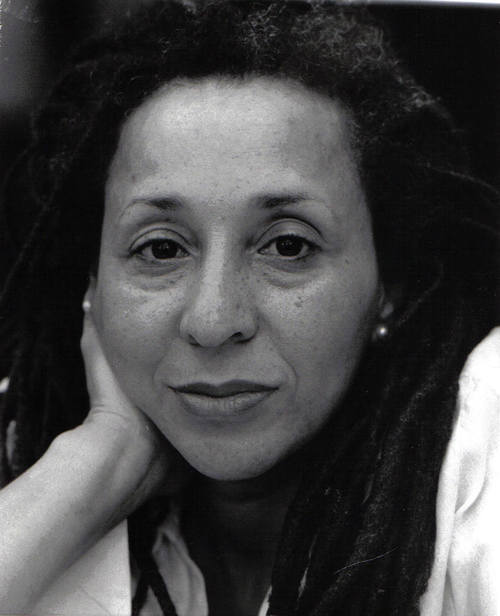

Jackie Walker is Vice Chair of Momentum Steering Committee.

Shami Chakrabarti’s Inquiry into Anti-Semitism and Racism in the Labour Party made big news soon as it was published – and for all the wrong reasons, just one of the ongoing consequences of the “occasionally toxic atmosphere” that is “in danger of shutting down free speech within the Party rather than facilitating it.” Chakrabarti makes it clear her intention is not to “close down debate on delicate issues around all kinds of personal and political differences within the Party” but to conduct these debates “in a more trusting and constructive environment.” My response is made with the same intent.

As a recently suspended Labour Party member, and the only person as yet (at the point of writing) exonerated, I was bound to read Chakrabarti’s report, and the coverage that followed, with more than a little interest. I write as a long time Labour Party and anti-racist activist for whom Chakrabarti’s findings are personally and politically important. My partner is Jewish, his family observant, but I comment as a woman of mixed Jewish and other heritages who identifies as, and is perceived by others as, a black person of African descent.

Much of the mainstream media response to the Inquiry focused on anti-Semitism, was superficial, poorly informed or with one intent – destabilising Labour and its present leadership. Chakrabarti’s generally well expressed ‘state of the Party’ contextualisation of race relations, and her many well thought through and sensible recommendations, were sidelined as charges of anti-Semitism yet again took centre stage, immediately undermining the Inquiry’s key findings on BAME (Black and Minority Ethnic) members.

At the core of the debate is the way competing claims by minorities are positioned in the (at this point in time) supercharged arena of Labour Party politics. In the political arena, perhaps more than elsewhere, race is about power – who has it, who is chosen to represent the Party, who gives power to others and how that power is communicated. Two areas are highlighted in the part of the Chakrabarti Report that focuses on BAME members – that of representation and vocabulary.

Chakrabarti begins with evidence; that in 2010 the BAME community voted for Labour more than double in relation to whites. She describes an unwelcoming environment and a lack of representation at all levels, including in Parliament, but also in the administrative structures of the Party, singling out the lack of black members in the NEC for special mention. What an irony then that it is the voices of people of colour, in particular those of African descent, that were so effectively sidelined in reporting of the Inquiry.

In today’s Labour Party Chakrabarti situates anti-Semitism within a set of feelings and responses as reported in many submissions by some in the Jewish community. Stereotypes limit the ability of peoples to be treated and respected as individuals and Chakrabarti’s comments on the need for sensitivity in the language of debate, whether on issues that relate to Israel or elsewhere, are to be welcomed. But there is acknowledgement that it is power, or the lack of it, that excludes and discriminates against BAME people in the Party, as it does of course in the rest of society. Blacks do not only feel under-represented, or stereotyped in the Party. They are under-represented. They may be members and supporters, they are of course, particularly in Labour’s urban heartlands, often the foot soldiers and voters, but BAME members are effectively excluded where it matters – from power.

Given the terms Chakrabarti was given for her inquiry it is difficult to see how this could have been avoided. If anti-Semitism is set apart from ‘other forms of racism’, can we be surprised when the Inquiry fails to attract a significant number of submissions from BAME groups, or when black individuals are significant only by their absence at its launch? The reception of the Inquiry in the media and elsewhere simply underlined the powerlessness of the BAME community. The paucity of any black response, at a national level, confirms the exclusion the report attempts to redress. In this three card trick discrimination against BAME members is the card that appears, I hope only for the moment, to have been made to magically vanish.

I come now to the issue of vocabulary, in particular comments on the use of the term ‘holocaust,’ a point that concerns many people of African descent who await both recognition or recompense for past wrongs inflicted.

Chakrabarti makes plain her Inquiry is an attempt to bring people together. To stand in solidarity, as Chakrabarti suggests all minorities need to, people of African descent must see the structures that exclude them from power, and have kept them silenced for so long, being changed. This is the only way in which attempts to build an inclusive Party will succeed.

Groups that have suffered oppression need to have conditions, a level playing field, in which they can form united political fronts, working in solidarity with others, rather than having to fight for a place at the table, forever bogged down in disputes about equity, access to power, or the meaning of the past. If the Party does not succeed in this, Labour will remain entangled in the impossible task of being a moral referee as minority ethnic groups engage in a ‘competition of victimhoods’ in order to gain, build or protect recognition.

Others have argued elsewhere for dropping the use of the contested terminology of ‘holocaust’ and replacing it with ‘genocide’. Some suggest opening Holocaust Day more fully to all communities that have suffered mass murder. As Jews retain the word Shoah, so peoples of African descent refer to Maangamizi for their holocaust. Maangamizi describes the slave trade and history of enslavement when millions of Africans were killed, tortured, kidnapped and enslaved for profit but it also refers to the genocides and deprivations of colonialism and the ongoing, consequential suffering and oppressions of peoples of African descent.

I am in agreement with Chakrabarti there are, and can be, no hierarchies of suffering. The Inquiry rightly warns of dilution of effect ‘if every human rights atrocity is described as a Holocaust’. However, I cannot see the term ‘holocaust’ as something the Labour Party can, or should police, though it may provide a useful forum where terminology can be discussed. As ever, the Labour Party must recognise the right of minorities to both name themselves and choose how their history is narrated.

It is in the ability of the labour movement to listen to the experience of people of African descent and other BAME peoples where I now place my trust. It is with hope that I ask that our leaders listen to the concerns of people of colour whose voices before and during the Inquiry, and even now, remain barely heard. I look forward to the changes to come.

On 29th April, as the media hyped ‘anti-Semitism’ hysteria in the Labour Party was in full swing, with daily revelations from those doughty fighters against racism at the Daily Mail, Jeremy Corbyn set up an inquiry into racism in the Labour Party under the former Chair of Liberty, Shami Chakrabarti. Chakrabarti is no radical and when it was announced that Baroness Royall of Labour Friends of Israel was to become a Vice Chair of the Inquiry I

On 29th April, as the media hyped ‘anti-Semitism’ hysteria in the Labour Party was in full swing, with daily revelations from those doughty fighters against racism at the Daily Mail, Jeremy Corbyn set up an inquiry into racism in the Labour Party under the former Chair of Liberty, Shami Chakrabarti. Chakrabarti is no radical and when it was announced that Baroness Royall of Labour Friends of Israel was to become a Vice Chair of the Inquiry I

IRR’S

IRR’S