The Independent Jewish Voices Steering Group has made a submission to the Shami Chakrabarti Inquiry into antisemitism and other forms of racism within the Labour party.

The Independent Jewish Voices Steering Group has made a submission to the Shami Chakrabarti Inquiry into antisemitism and other forms of racism within the Labour party.

It is a comprehensive response to the key question for the Inquiry: When does an individual’s critical comment on Israel and/or Zionism constitute antisemitism? It explains that the post-Second World War consensus on what constitutes antisemitism has broken down and since the early 1980s, Israel has been promoted as the central object of antisemitic hate. The submission looks at how the late nineteenth century Zionist political movement developed conflicting strands, and today Zionism follows the path of maximalist nationalism and settler colonialism, driven largely by right-wing politicians, rabbis and settlers pursuing an ethnoreligious, messianic and exclusionary agenda.

A summary can be found on their website here.

The full submission prepared by Antony Lerman with the IJV Steering Group* can be viewed and downloaded here: IJV SG submission to Chakrabati Inquiry 10 Jun 16. We strongly recommend you read it in full.

Below are excerpts only:

2.0 HOW THE SHARED UNDERSTANDING OF ANTISEMITISM HAS BEEN UNDERMINED

2.1 For those who have been studying and combating antisemitism for decades, it’s hard to believe that anyone born since the end of the Cold War hasn’t known a time when Israel was not at the centre of discussions about the state of current antisemitism. But there is clear evidence that, broadly speaking, 40 years ago there was still a shared understanding of what antisemitism was. And Israel was hardly ever mentioned. True, historians differ over a precise definition—quite understandably, given that the term was coined only in the 1870s, and was then used to describe varieties of Jew-hatred going back 2,000 years. But, in practice, during the first three or four decades after the Second World War, antisemitism was commonly linked to the classical, negative, dehumanising stereotypical images of ‘the Jew’ forged in Christendom, adopted and adapted by antisemitic political groups in the nineteenth century and further developed by race-theorists and the Nazis in the twentieth century. That process of reformulation and revision did not end with the Holocaust. The most significant development in antisemitism after 1945 was the rapid emergence of Holocaust denial. Interestingly, while it seems some began to refer to this as the ‘new antisemitism’, most researchers and academics analysing and writing about the phenomenon had no difficulty in seeing it as essentially a new manifestation of consensually-defined, multifaceted antisemitism.

2.2 Today, not only has that consensus broken down and Israel is promoted as the central object of antisemitic hate. Something much more far reaching has occurred. A fundamental redefinition of antisemitism has taken place. And the term that most fully encapsulates this redefinition is ‘new antisemitism’, which began to come into vogue and gain traction in discussions about contemporary antisemitism from the end of the 1970s. Yet it only gained status as the dominant narrative in such discussions after the turn of the century when certain events appeared to give credence to the notion that antisemitism, mainly manifested in critical discourse on Israel and Zionism, was significantly resurgent worldwide. These events included the collapse of the Camp David negotiations in July 2000 (presented by Israel and its most enthusiastic supporters as a Palestinian betrayal), the outbreak of the second Palestinian intifada in the autumn and the anti-Israel and anti-Jewish manifestations at the UN Conference on Racism in Durban in August-September 2001, and they were all claimed to be evidence of a deeply rooted, extreme, irrational anti-Zionism, seen by outspoken supporters of Israel as conclusive proof that the country was now incontrovertibly the ‘Jew among the nations’. When the New York Twin Towers were destroyed on 11 September and conspiracy theories soon emerged laying the blame on ‘Jews’ and ‘Zionists’, this event too was used to validate the ‘new antisemitism’ notion. Since then, increasingly politicised arguments about the validity of the term have raged back and forth.

2.3 But in recent years we find it being used more infrequently, not because in the court of academic or popular opinion the term has been deemed inappropriate. On the contrary. ‘New antisemitism theory’, as it is sometimes called, has become increasingly embedded in understandings of antisemitism that essentially see anti-Zionism and antisemitism as one and the same. It has therefore become less necessary for the proponents of this concept to qualify this understanding of what antisemitism is with the word ‘new’.

2.4 We see this in the seemingly unstoppable dissemination of the so-called ‘working definition’ of antisemitism originally posted on the website of the now defunct European Monitoring Centre on Racism, Xenophobia and Antisemitism (EUMC) in 2005, a ‘definition’ that fleshes out what constitutes ‘new antisemitism’, in other words where comment on Israel and Zionism can be deemed antisemitic, by providing five so-called examples of this kind of discourse. (The full text of the so called ‘working definition’ can be accessed here.) However, it is an undisputed fact that the EUMC never formally adopted this definition, that it merely offered it for discussion, that its successor organization, the EU’s Fundamental Rights Agency (FRA) did not put it on its website and, furthermore, categorically stated that it was not using this definition in its work and would not be endorsing it in any way.

2.5 Nevertheless, those who have supported and drawn on this ‘working definition’ since its inception refuse to acknowledge that it has no official standing and they continue to propagate it, often omitting the ‘working definition’ qualifier and describing it erroneously as the, formal EU definition of antisemitism. Most recently, almost the entire ‘working definition’ has been subsumed into a new ‘working definition’ issued by the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) and announced in a press release issued on 27 May. (The IHRA, founded in 1998, describes itself as ‘a body of 31 Member Countries, ten Observer Countries, and seven international partner organisations, with a unique mandate to focus on education, research and remembrance of the Holocaust’. The press release states that the IHRA is supported by the Foreign and Commonwealth Office.)

2.6 It is therefore important to understand that the controversy over whether anti-Zionism is antisemitism is not unique to the Labour Party, or to the left in general, or to the advent of the Corbyn leadership, but dates back at least three or four decades. Widespread Western sympathy for Israel and Zionism began to erode in the wake of the 1967 war. Israel’s occupation of Palestinian land and its emerging apparent reluctance to withdraw from it, in part made manifest by the growing movement to establish Jewish settlements beyond the 1967 Green Line, provoked growing organized opposition, particularly on the part of the Palestinians, but also among left-wing groups in the West. At the same time, the adoption of UN General Assembly resolution 3379 in 1975 that said ‘Zionism equals racism’, largely at the instigation of the Soviet Union and supported by its client states, caused considerable disquiet in Jewish and non-Jewish pro-Israel circles.

2.7 In the UK these developments generated much discussion within the organised Jewish community, but the focus of attention was on the erosion of liberal support for the Jewish position and on a largely academic discussion about the relationship between anti-Zionism and antisemitism, about which there was considerable, reasoned disagreement. But in the following two decades, those discussions took on an increasingly political and polemical character as the notion of the ‘new antisemitism’ developed.

2.8 The ‘new antisemitism’ has been clearly defined by one of its earliest, leading and most assiduous proponents, the Canadian professor of law and former minister of justice in the 2003-6 Liberal government, Irwin Cotler: In a word, classical anti-Semitism is the discrimination against, denial of, or assault upon the rights of Jews to live as equal members of whatever society they inhabit. The new antiSemitism involves the discrimination against, denial of, or assault upon the right of the Jewish people to live as an equal member of the family of nations, with Israel as the targeted ‘collective Jew among the nations’. (National Post, Toronto, 9 November 2010)

2.9 As Israeli and Jewish-organized pro-Israel activity expanded and strengthened in response to the growing international criticism of Israel, the ‘new antisemitism’ formulation was found to be ever more useful. It provided a seemingly logical and plausible basis for branding anti-Zionism as inherently antisemitic. It strengthened the argument that the Arab world’s hostility to Israel was rooted in antisemitism. And it pinned the antisemitic label also on the political left, anti-globalization movements, jihadist and Islamist movements and the Muslim world more generally, the Palestinian Solidarity Campaign, the left-liberal press, anti-racist groups—the list is long. It further provided the platform for the formulation of the EUMC ‘working definition’, which in its turn was in part the basis of the US state department’s definition of antisemitism, now being used to stifle debate about boycott, divestment and sanctions (BDS) on US university campuses. And from the beginning of the twenty first century, Israeli governments dramatically increased their involvement in gaining international acceptance of the ‘new antisemitism’, both by bolstering Jewish communal approval of the notion and raising it in bilateral as well as multilateral discussions with other countries. When the EUMC ‘working definition’ entered the public domain in 2005, the Israeli government lost no time in making use of it to deflect criticism of its behaviour.

2.10 The process by which the shared understanding of what constituted antisemitism was undermined was multifaceted. But in the UK, three crucial elements of that process were: the increasing popularity of ‘new antisemitism theory’; the propagation of the EUMC ‘working definition’; and a misreading of the Macpherson inquiry’s definition of a racist incident as ‘any incident which is perceived to be racist by the victim or any other person’, and is now the definition used by police when antisemitic attacks are reported. This has been and still is being used by some Jewish groups as justification for claiming that Jews alone should be able to define what antisemitism is.

2.11 ‘New antisemitism’ There are three fundamental flaws in the concept of the ‘new antisemitism’.

2.11.1 First, ‘new antisemitism theory’ contains the radical notion that to warrant the charge of antisemitism, it is sufficient to hold any view ranging from criticism of the policies of the current Israeli government to denial that Israel has the right to exist as a state, without having to subscribe to any of those things which historians and social scientists have traditionally regarded as making up an antisemitic view: hatred of Jews per se, belief in a worldwide Jewish conspiracy, belief that Jews generated communism and control capitalism, belief that Jews are racially inferior and so on. Given that the definition of the ‘new antisemitism’ is fundamentally incompatible with any definition relying on elements which historians accept make up an antisemitic view, for anyone who agrees with the definition of the ‘new antisemitism’ it’s but a short step to conclude that it replaces all previous definitions and then further to argue that no other kind of antisemitism exists. (Given the resurgence of traditional forms of antisemitism in Europe today, such an argument is preposterous.) This is the fundamental redefinition of antisemitism referred to above.

2.11.2 Second, the formulation takes no account of the fact that the creation of the state of Israel gave Jews collective power of a kind they had not had for 2,000 years. Broadly-speaking, Jews went from being the objects of history to being history’s subjects, able to act in the modern world to control the Jewish fate as never before and, by Israel’s policies, to control the lives of minority groups in its midst and impact the fates of states adjacent to it. And like every other state, its policies, constitutional arrangements and human rights behaviour are therefore rightly subjected to scrutiny.

2.11.3 Third, while it sounds plausible to set up ‘the individual Jew’ and ‘the collective Jew’ as comparable categories and equate the hostility experienced by both, it is a category error to do so. A state is an amoral institutional framework for organizing the lives of all those who live within it. An individual is a sentient human being ultimately at the mercy or otherwise of the state. A state is not a human being writ large. With Palestinian Arabs making up 20 per cent of its population, and its Jewish population very diverse and multicultural, to describe the state as ‘the collective Jew’ is a nationalist myth. It further dehumanises the Palestinian minority, making it easy to turn legitimate criticism of the state for its treatment of them into an antisemitic assault.

2.12 The EUMC’s ‘draft working definition’ of antisemitism

Turning to the EUMC ‘working definition’ (hereafter ‘WD’), it is worth first pointing out that its url on the EUMC’s website always carried the word ‘draft’. We highlight here two of its fundamental flaws:

2.12.1 According to the definition of a definition, the ‘WD’ is not a definition. The Merriam Webster dictionary defines the word ‘definition’ to mean ‘a statement expressing the essential nature of something’ or ‘the statement of the meaning of a word’. The EUMC document, running to 514 words, cannot be considered as expressing only the essential nature or meaning of the word ‘antisemitism’.

2.12.2 The ‘WD’ contains 2 lists of ‘contemporary examples of antisemitism’. The first list is relatively unproblematic. The second, headed ‘ways in which antisemitism manifests itself with regard to the state of Israel taking into account the overall context’, provides 5 examples, 4 of which are highly contentious.

2.12.2a One is ‘Denying the Jewish people their right to self-determination’. But denying the right of a people to self-determination is by no means uncommon and can be justified on various non-racist grounds. Here are a few examples. First, while the notion that ‘people’ living in a certain region where there is or has been a common language and historical experience have the right to self-determination in the sense of deciding on how they should be democratically governed, this does not legitimise ceding such a right to ‘a people’ or a ‘nation’. The establishment of the devolved assembly in Wales illustrates this. Second, the argument against a people’s right to self-determination could be made on anti-racist grounds given that self-determination for one national group within a particular territory very often involves denying rights to other minority peoples/national groups within that territory. Finally, while states containing a number of national groups often face political difficulties arising out of the justified or unjustified claims made by those groups, the central state authority could reasonably claim that giving one such group the right to self-determination might destabilise the state, unleashing forces that are difficult if not impossible to control, and result in violence and civil war. The point is that denying a people the right to self-determination could be racist—one such example would be saying Jews have no such right because they are ‘sub-human’ or because they will use their status to ‘unleash their unique evil upon the world’—but it could be many other things.

2.12.2b The other 3 examples in the ‘WD’ are similar: they could be antisemitic, but there could be various reasons why they are not. One example not included is ‘support for the existence of the state of Israel’—and yet there have always been antisemitic advocates of Zionism: Lord Arthur Balfour, for example, the British Foreign Secretary who announced the government’s approval of a home for the Jews in Palestine in 1917 in what came to be known as the Balfour Declaration. In 1905, he strongly supported proposed legislation to restrict Jews from Eastern Europe immigrating into Britain. The fundamental problem here is that a definition of prejudice relying on a number of examples contains a fatal flaw: practically any statement about the group concerned might be construed as racist, but then again, it might not be. To proceed in this way is of no help in identifying racism or antisemitism. A definition is only useful if it provides you with the general analytical tools with which to assess a statement or an act. Simply to say x ‘could’ be antisemitic is the same as saying x ‘could’ not be antisemitic. You might as well say nothing at all.

2.13 The Macpherson Report’s definition of a ‘racist incident’

2.13.1 The report of the Macpherson inquiry into the death of the Black teenager Stephen Lawrence defined a racist incident as: ‘any incident which is perceived to be racist by the victim or any other person’. This has been widely interpreted as a comprehensive definition of racism, meaning that only the group that experiences racism is entitled to define what that racism consists of. In other words, only Jews can define what antisemitism is because they are the ones who experience it. We find this argument repeated constantly by some of the Jewish organisations that claim responsibility for the 10 defence of the Jewish community, and by some parliamentarians who are outspoken in the issue of antisemitism. But while it would be highly unlikely that any person concerned about the problem of antisemitism, whether they are Jewish or not, would disagree with the fundamental principle that the voice of someone who believes they have been the victim of an antisemitic attack must be heard and must be paramount, there is no consensus among Jews as to the definition of an antisemitic attack and no consensus on what antisemitism is more generally. Continue reading “Independent Jewish Voices submission to the Chakrabarti Inquiry”

The Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement calls for an economic, academic and cultural boycott of Israel over its policies towards the Palestinians. The UK, United States and other governments have criticised BDS as anti-Semitic and tried to prevent organisations, such as local authorities and student unions, from supporting it.

The Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement calls for an economic, academic and cultural boycott of Israel over its policies towards the Palestinians. The UK, United States and other governments have criticised BDS as anti-Semitic and tried to prevent organisations, such as local authorities and student unions, from supporting it. This is the most protean of racisms and it has shape-shifted again. Old-fashioned Jew hatred still exists, but anti-Semitism today is often found—as the Labour Party is discovering—in the smelly borderlands where an anti-Israeli sentiment of a particularly excessive, demented kind, commingles with and updates—often unthinkingly—older anti-Semitic tropes, images and assumptions.

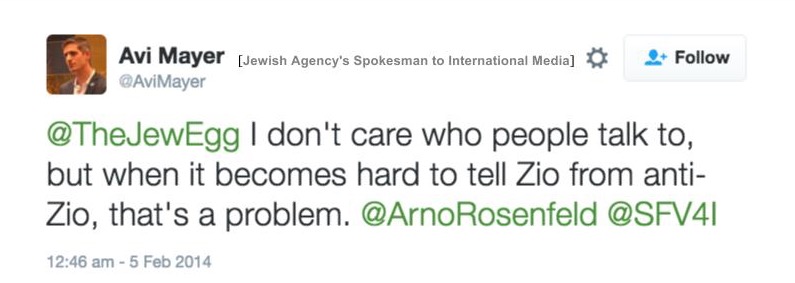

This is the most protean of racisms and it has shape-shifted again. Old-fashioned Jew hatred still exists, but anti-Semitism today is often found—as the Labour Party is discovering—in the smelly borderlands where an anti-Israeli sentiment of a particularly excessive, demented kind, commingles with and updates—often unthinkingly—older anti-Semitic tropes, images and assumptions. You do go to rhetorical extremes. I had hoped this exchange might calm and clarify an important debate. Setting up ghoulish straw men so that you can satisfyingly knock them down doesn’t hack it. I will try to practise what I preach. Your case, when stripped of the cartoon villains, comes down to a useful neologism; useful, that is, to you. I would like to dwell on “anti-Semitic anti-Zionism” as a concept.

You do go to rhetorical extremes. I had hoped this exchange might calm and clarify an important debate. Setting up ghoulish straw men so that you can satisfyingly knock them down doesn’t hack it. I will try to practise what I preach. Your case, when stripped of the cartoon villains, comes down to a useful neologism; useful, that is, to you. I would like to dwell on “anti-Semitic anti-Zionism” as a concept.

The Independent Jewish Voices Steering Group has made a submission to the Shami Chakrabarti Inquiry into antisemitism and other forms of racism within the Labour party.

The Independent Jewish Voices Steering Group has made a submission to the Shami Chakrabarti Inquiry into antisemitism and other forms of racism within the Labour party.