Republished from Open Democracy

A cavalier use of evidence in the UK’s latest Home Affairs Select Committee report is feeding a moral panic about antisemitism, rather than dealing with an increasingly racist, intolerant society.

The latest report by the House of Commons Home Affairs Committee (HAC) Antisemitism in the UK Tenth Report of Session 2016–17 , was released to great fanfare on Sunday 16 October. Its accompanying embargoed press release, headed “All Parties – And Media Giants – Must Address ‘Pernicious’ Antisemitic Hate”, led with the following note: “[T]he failure of the Labour Party consistently and effectively to deal with antisemitic incidents in recent years risks lending force to allegations that elements of the Labour movement are institutionally antisemitic.”

Against a background of rising criticism of the Israeli state and its actions, attempts have been made in recent decades to redefine our understanding of antisemitism to include much of this criticism under the rubric of what is labelled “left antisemitism”. Genuine antisemitism and criticism of Israel which “oversteps the bounds” are rolled up into one and the same thing. In recent months the British Labour party has become the focus of attention as the exemplar, par excellence, of this “left antisemitism”.

In this respect the publication of the Chakrabarti report at the end of June was an important moment not just for the Labour party. It was a model of careful language, civility and empathy. Chakrabarti didn’t accuse anyone of bad faith, and strove to engage with the real pain that has been caused to people involved on all sides in this issue so far. It seemed to herald the possibility of moving beyond the fractious and divisive use of antisemitism as a political football which has so dogged debate in recent years. That is why I am dismayed to see the direction and trend of the latest Home Affairs Committee report (hereinafter called “the Report” and its author referred to as “the Committee”; all references to “paras” are to paragraphs in the report).

I want to comment particularly on the following areas of the Report:

a) its obsessive focusing on Labour

b) its shameful rubbishing of Chakrabarti

c) its confusions over “Zionism”

d) its attempt to (re)define antisemitism (including a misrepresentation of a definition it says it is endorsing)

e) its insistence that antisemitism is special, not like other racisms.

Demonising the Labour party

“It should be emphasised that the majority of antisemitic abuse and crime has historically been, and continues to be, committed by individuals associated with (or motivated by) far-right wing parties and political activity. Although there is little reliable or representative data on contemporary sources of antisemitism, CST [Community Security Trust] figures suggest that around three-quarters of all politically-motivated antisemitic incidents come from far-right sources.” (para 7)

Since obsessive focusing on Israel is taken by many as an indication of antisemitism, what do we make of the Committee’s obsessive focusing on the UK Labour Party, on Shami Chakrabarti, and on the world of student politics?

We might expect that three-quarters of the report would focus on the “antisemitic incidents com[ing] from far-right sources”. But that paragraph is about the only attention paid to the right in its 66 pages. Only 6 paragraphs (paras 121-126) look at antisemitism in relation to any political parties, other than Labour.

Further, there is no reference to the rampaging resurgence of all forms of racism in British political life, an openly racist Tory campaign for the London mayoralty, a Prime Minister referring to refugees in Europe as “a swarm” and accusing Labour of encouraging “a bunch of migrants” at Calais to come to Britain, and of course the post-Brexit referendum surge of hate crimes. Why is there no reference to this context?

Instead the report aims to “differentiate explicitly between racism and antisemitism (Report, para 114)” arguing that they are two different kinds of animal. Why?

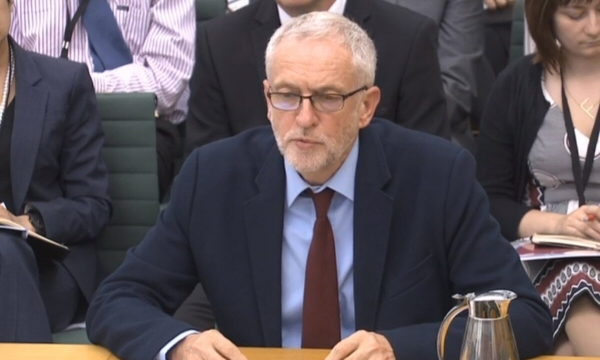

As Jeremy Corbyn pointed out, in a mastery of understatement: “The report’s political framing and disproportionate emphasis on Labour risks undermining the positive and welcome recommendations made in it.”

One area that does receive attention, the scale of verbal abuse on social media, Twitter in particular, is clearly disturbing, and the Report does well to draw attention to it. But again, the antisemitism which is found there cannot be an isolated concern. Other forms of racism, Islamophobia in particular, and a generalised culture of anti-immigrant hate speech, sexual harassment and bullying is passed over as of no particular consequence. Rather, the Committee simply seems to have assumed that a) abuse in this sphere all comes from the left and b) that it is somehow licensed by what it claims to be Corbyn’s light-hearted attitude to antisemitism.

Nowhere is this clearer than with regard to Ruth Smeeth MP who is said to have experienced “more than 25,000 incidents of abuse, including being called a “yid c**t” and a “CIA/Mossad informant”, and who has said that she has “never seen antisemitism in Labour on this scale”. What percentage of the 25,000 were antisemitic we are not told, though Ms Smeeth’s own statement on television is reported: “It’s vile, it’s disgusting and it’s done in the name of the Leader of the Labour party, which makes it even worse” (Report, para 104). But was it done in Corbyn’s name? What’s the evidence for that assertion? How many of these tweeters were left-wing Labour? Did the Committee bother to ask? There is no evidence it did so. It seems to have operated on the generalised, taken-for-granted assumption that as antisemitism is rampant in the Labour party that’s where it must have come from. And it simply ignores the fact that Corbyn “contacted Ruth Smeeth to express his outrage at the abuse and threats directed against her” (or that the Sun chose to headline this action as “Jeremy Corbyn grovels to race-hate row MP Ruth Smeeth”!).

How can this explain what happened to Rhea Wolfson, a Jewish member of the party who stood for the NEC only to be (temporarily) blackballed on the grounds that she was supported by Momentum, allegedly “an antisemitic organisation”. Tweets sent to her in early October included: “1 way ticket to Auschwitz for you” and “Dirty kike she ready for the ovens” (Rhea Wolfson press release, 16 Oct 2016). It beggars belief that these tweets were sent to her by left-wing Labour supporters.

This does not appear to be a mere a lack of curiosity in the Report. On the contrary. Its authors seem positively to want to lend support to the idea of Labour’s “institutional antisemitism”, mentioned in the very first paragraph of its press release. The ‘Macpherson definition’ of a racist incident is cited in para 13 – as though the Metropolitan police’s unwillingness to recognise racism in the past is equivalent to Labour’s relationship to antisemitism today. You wouldn’t guess from the Report that every allegation of antisemitism in the Labour party has resulted in the suspension of the Labour party member concerned within a matter of days and that its leader has repeatedly and unreservedly condemned antisemitism. Given this absence, which was compounded by the way the Report was presented to the media, it is no surprise that all outlets duly led with its attack on Labour and focused on Jeremy Corbyn’s alleged “lack of leadership” and “weakness” in dealing with the assumed scourge of antisemitism in his movement.

Corbyn’s immediate response was a cautious, even gracious, welcome (“I welcome some recommendations in the report, such as strengthening anti-hate crime systems, demanding Twitter take stronger action against antisemitic trolling and allow users to block keywords, and support for Jewish communal security”), together with a clear recognition of what he politely calls “important opportunities lost” in the report.

Corbyn also pointed out that: “Under my leadership, Labour has taken greater action against anti-Semitism than any other party, and will implement the measures recommended by the Chakrabarti report to ensure Labour is a welcoming environment for members of all our communities.”

Critique of Chakrabarti

The Home Affairs Committee seems to have been almost equally obsessed by a desire to discredit the Chakrabarti Report and some effort is made to discredit Shami Chakrabarti personally in circumstances in which she has no right of reply.

She is, for example, shamelessly taken to task for having joined the Labour party and also for subsequently having accepted a peerage (which she should long ago have had for her public service if peerages mean anything at all). The Community Security Trust (CST) is quoted as saying it was “a shameless kick in the teeth for all who put hope in her now wholly compromised inquiry into Labour antisemitism” (para 108). “Wholly compromised” is strong condemnation indeed – but nothing in the Report suggests or even hints at how or in what way anything in her inquiry was compromised. The CST were not asked what had changed to undermine their guarded welcome for the Report at the time it appeared, which including saying, “Many of our recommendations are echoed in the final report’s language concerning Zionism, the term ‘Zio’ and Holocaust analogies”; and also made the point that “The final verdict on the Chakrabarti Report will depend upon its implementation.”

The Committee’s report goes on to claim that the Chakrabarti inquiry was “ultimately compromised by its failure to deliver a comprehensive set of recommendations, to provide a definition of antisemitism, or to suggest effective ways of dealing with antisemitism (para 118).

I’ll come to the separate issue of a definition of antisemitism below, including in the Chakrabarti Report. But Chakrabarti did, of course, provide a comprehensive set of recommendations and suggested ways of dealing with antisemitism. They need to be implemented and only then can their effectiveness at dealing with antisemitism over time by judged. How can it be anything other than partisan bias for the Committee to dismiss them at this stage?

In particular, Chakrabarti was very explicit about the need for clear and transparent disciplinary procedures in the Labour party in order to deal with allegations – this in a context where there was widespread feeling that allegations of antisemitism were being used as weapons in a campaign to get Corbyn. A significant part of her report –as yet unimplemented – relates to issues of due process and natural justice. None of this is given more than a hint of recognition by the Home Affairs Committee (para 114).

Yet this really does matter. A number of accusations of antisemitism, of varying degrees of severity, have been made against members of the Labour party who have been suspended as a consequence – without due process, without knowing sometimes what they are accused of, who by or why. The Report fails to take note of the strong evidence produced that at least some of the accusations of Labour party antisemitism were malicious and their timing, beyond a shadow of doubt, politically motivated. All these accusations against Labour party members are assumed by the Report and the media to be clearly established instances of the extreme antisemitism that Labour is riddled by. But some we know to have been false and some exaggerated.

In the end, this selectivity of narrative and treatment does a disservice to any genuine fight-back against antisemitism. Here it is particularly concerning that the report was signed off by two members of the Labour party (who, by the way, have a clear anti-Corbyn agenda) without appearing to express any concern about the need to investigate and clear up the accusations of antisemitism in their own party as a matter of urgency. But that can only be done when proper procedures are in place – as Chakrabarti’s maligned report insisted. As Tony Klug pointed out writing in the Jewish Chronicle on 5 May in The problem is real but exaggerated: “While antisemitism is monstrous – and, like all forms of racism, should be vigorously dealt with – false accusations of antisemitism are monstrous too.”

On a different note, it is undoubtedly true that while a few of the reported instances of antisemitism in and around the Labour party relate to classic antisemitism, most would appear to be connected with Israel and/or the ongoing war over Gaza. This is something the Committee seems to have failed to look into at all – though its obsession with a definition of antisemitism (see below) suggests that it is happy to allow these key distinctions to be elided.

Here the need to be able to have an open, wide-ranging and honest discussion about Israel and Palestine is clearly crucial. And here the Committee’s intervention is not at all helpful, asserting without evidence of widespread “unwitting” antisemitism on campus “and within left-leaning student political organisations in particular” (Report, para 93). I won’t comment on this alleged campus antisemitism section except to draw attention to the Open Letter to Home Affairs Select Committee sent within hours of publication of the report, signed by over 300 students, which claimed: “[W]e believe this report’s selective and partisan approach attempts to delegitimise NUS, and discredit Malia Bouattia as its president [by suggesting she does not take the issue of campus antisemitism seriously]. An attack on NUS is an attack on the student and union movements. This is completely unacceptable and we cannot allow these claims against us to go unchallenged.”

Compare Chakrabarti’s lucid contribution in her report with that of the Home Affairs Committee: “This is not to shut down debate about what has been one of the most intractable and far-reaching geopolitical problems of the post-war world, but actively to facilitate it. Labour members should be free and positively encouraged to criticise injustice and abuse wherever they find it, including in the Middle East. But surely it is better to use the modern universal language of human rights, be it of dispossession, discrimination, segregation, occupation or persecution and to leave Hitler, the Nazis and the Holocaust out of it? This has been the common sense advice which I have received from many Labour members of different ethnicity and opinion including many in Jewish communities and respected institutions, who further point to particular Labour MPs with a long interest in the cause of the Palestinian people with whom they have discussed and debated difficult issues and differences, in an atmosphere of civility and a discourse of mutual respect.” (Chakrabarti p. 12)

Opposing Zionism

Curiously, the Committee report echoes much of Chakrabarti in relation to discourse, but while Chakrabarti is forward-looking and educational (see quote above), the Committee’s approach is punitive.

Chakrabarti’s condemnation of the use of certain language inveighed, rightly, against any “bitter incivility of discourse”, including her insistence that there was no place for the use of the word “Zio” ever, nor for “Zionist” as a term of abuse (recommendations accepted by the Labour party’s NEC in September). These are snidely dismissed by the Report (para 102) as “little more than statements of the obvious”. And yet lo, in para 32 of the Report we have this: “The word ‘Zionist’ (or worse, ‘Zio’) as a term of abuse, however, has no place in a civilised society… [Their use] should be considered inflammatory and potentially antisemitic.” It is hard to tell the Committee’s and Chakrabarti’s formulations apart, as the words are transmogrified into no longer being “little more than statements of the obvious”.

The Committee seems clear that “’Zionism’ as a concept remains a valid topic for academic and political debate, both within and outside Israel” (para 32). But not really. Rabbi Mirvis’s opinion is given that “Zionism has been an integral part of Judaism from the dawn of our faith”. Mick Davis of the Jewish Leadership Council is quoted as saying that criticising Zionism is the same as antisemitism for “if you attack Zionism, you attack the very fundamentals of how the Jews believe in themselves” (paras 26 & 27).

The report is insistent that in a recent survey, 59% of Jews saw themselves as Zionist. Assuming this is the case, it still does not make Zionism a protected characteristic of Jewish identity. What if opinion among these people changed? Would their becoming anti- or non-Zionist now become a heretical position which the Jewish community could use to exclude members from it as no longer adhering to “the very fundamentals of how the Jews believe in themselves”? What indeed to make of the current 41% of the Jewish population who don’t identify as Zionist? Are they not real Jews as far as the Chief Rabbi or Mick Davis are concerned? The Report just leaves these contradictory strands hanging – giving the overwhelming impression that these are too complicated for ordinary mortals. Better leave them as no-go areas.

Surely it is self-evident that Jews see themselves in multiple and contradictory ways? So any attempt to let Jews self-define what is or is not antisemitic soon runs into an impossible impasse – which Jews are accorded the franchise to define where other Jews may tread (especially when some sections of that community find almost any criticism of Israel likely to cause offence)?

At every stage, the Committee buys into the view that criticism of Israel is a dangerous place to go. “It is clear, “says the Report that where criticism of the Israeli Government is concerned, context is vital.” And how does the Report contextualize it? “Israel is an ally of the UK Government and is generally regarded as a liberal democracy, in which the actions of the Government are openly debated and critiqued by its citizens.” (Conclusions, para 2). Does it follow that any criticism by outsiders is likely to be offensive? Whatever happened to treatment of minorities as a benchmark of a healthy democracy?

Indeed the Report cautions not simply against using Zionism as a term of abuse (as did Chakrabarti) but against using the term at all. Criticise “the Israeli government” not Zionists”, it says (para 32). And sometimes, indeed, this might be good advice. After all, the right to give offence does not translate into a duty to do so. But sometimes the use of terms like Zionism is coolly analytical and can’t just be done away with.

Palestinians – some 750,000 of them – were dispossessed by a movement calling itself Zionist. How can they, and by extension those who support Palestinian rights today, explain this history by criticising “the Israeli government”? How can they be expected simply to regard Zionism as the timeless essence of a Jewish right to self-determination, above and beyond critique? Can anything be done in the name of Zionism without those who oppose it being allowed to name it?

Leaving aside the debate of what Zionism might or might not have been historically, ask what it has become. Only one strand of Zionism has any political purchase today, and it is not a pleasant one. Israel’s colonisation of the West Bank continues unabated. Green-line Israel’s discrimination against its increasingly second-class Palestinian citizens, and their physical displacement in the Negev, rolls on. What Israel now needs is to be judged by what it is doing. It is Israel’s actions that delegitimise it, not any antisemitism of the left. And these actions, carried out by and on behalf of the Israeli government, are called – by that government – actions on behalf of Zionism.

Of course the word “Zionist” can be a surrogate for “Jew” (just as the same danger, only a much more extreme variant, arises when Muslims are expected to distance themselves from acts of violent political Islam). Of course it can be used in an antisemitic manner. But it needs to shown to be the case, not simply assumed to be likely or, worse, read off from the very use of the term.

Of course holding all Jews responsible for what the government of Israel does is wrong – indeed antisemitic. But who makes the elision between Jews, Israel and Zionism more enthusiastically than the representatives of the Jewish Community when they stand by Israel, right or wrong and claim to support it in the name of all Jews?

This is the minefield that discourse on Israel-Palestine now has to negotiate on a daily basis but unfortunately the Home Affairs Committee has very little to say on how this can take place productively. Yet surely this is essential, not just in the democratic socialist party Labour aspires to be, but in our wider society where the parameters of debate can no longer be defined by a narrow elite. Again, Chakrabarti seems to have got this right: “We can facilitate free speech, whilst acknowledging the evidence that we have received that there have been some instances of undoubtedly antisemitic and otherwise racist language and discourse in the past and at the same time encouraging a civility of discourse which is respectful of each other’s diversity and sensitivities.” (Chakrabarti p.7)

This is simply good advice both to avoid giving unnecessary offence and to move forward. Incivility of discourse is to be deplored in its own right and because it is a counter-productive way of doing debate (and democracy), allowing discussion of the important issues to be sidetracked – and thus avoided. In this case it can feed a moral panic about antisemitism, rather than dealing with the real instances of antisemitism (in our increasingly racist and intolerant society), in a politically effective, open and productive way.

Redefining antisemitism

As already mentioned, one of the severe criticisms that the Report has now made of Chakrabarti is that she failed to define antisemitism (e.g. para 118). Leaving aside the fact that for most of the twentieth century what constituted antisemitism was not in doubt, the politicisation of the debate in recent decades has not helped and Chakrabarti might well have felt this minefield was better avoided.

Not the Committee, which insisted on jumping straight in, continuing a more than decade-long debate about how and to what extent criticism of Israel must be incorporated into a definition of antisemitism.

There has been a consistent attempt since around 2005, to get what was a draft of a “working definition of antisemitism” published on the website of the European Union Monitoring Centre for Racism and Xenophobia – one never endorsed by that body or its successor the Fundamental Rights Agency – adopted as the definition of antisemitism. I dealt with the history of this disputed definition at length some years ago in openDemocracy, and refer readers to the argument developed there.

In summary, suffice it to say here this document produced a “working definition”:

Antisemitism is a certain perception of Jews, which may be expressed as hatred toward Jews. Rhetorical and physical manifestations of antisemitism are directed toward Jewish or non-Jewish individuals and/or their property, toward Jewish community institutions and religious facilities.(emphasis in the original)

For clarification, this was illustrated with eleven examples of what “could, taking into account the overall context” be antisemitic. About half of the examples cited were concerned not simply with Jews but with how Israel was referred to.

The trouble is that the definition is so vague as to be useless as the practical operational tool that was being sought at the time by the EUMC. The eleven examples provided of what “could, taking into account the overall context” be antisemitic, don’t resolve the problem. If they could be antisemitic, equally they might not be… No EU member state adopted the document and the Fundamental Rights Agency quietly laid it to rest, removing it from its website.

The All-Party Parliamentary Committee on Antisemitism which in 2006 had pressed for the government to adopt the definition had, by 2015 decided otherwise (Report, Feb 2015, paras 9-11). It looked as though this highly controversial definition was recognised as simply unhelpful in the wider discussion of combatting antisemitism.

But the draft EUMC “working definition” took on a life of its own – as an ideological weapon to beat those who criticise Israel “too harshly”. Although it included the qualifier “could, taking into account the overall context” be antisemitic, there is in it nonetheless an underlying presumption that criticism of Israel is likely to be antisemitic unless proved otherwise.

Now the Home Affairs Committee has resurrected this draft working definition (in the form adopted almost verbatim by the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance and referred to as the IHRA definition). It notes the objections but simply says “We broadly accept the IHRA definition, (para 24. and recommend (Conclusion, para 4) that it “should be formally adopted by the UK Government, law enforcement agencies and all political parties” with two caveats – see below).

But the Committee distorts the document in a crucial way. It claims (para 17) that the list of illustrative examples are antisemitic. It simply drops the all-important qualification, that they might, “taking into account the overall context”, be antisemitic.

Was this done deliberately? One hesitates to suggest it as it would then be utterly dishonest. Or was it simply incompetence? If so it is of a high order. In any event it is astonishing that no-one on the Committee, or commentators to date, have remarked on it.

In deference to representations made by “the Friends of Palestine” (para 21, a vague identification not clarified further in the Report) the Committee proposes to add two caveats to its (misrepresented) account of the IHRA definition, and says:

[T]o ensure that freedom of speech is maintained in the context of discourse about Israel and Palestine, without allowing antisemitism to permeate any debate, the definition should include the following statements:

- It is not antisemitic to criticise the Government of Israel, without additional evidence to suggest antisemitic intent.

- It is not antisemitic to hold the Israeli Government to the same standards as other liberal democracies, or to take a particular interest in the Israeli Government’s policies or actions, without additional evidence to suggest antisemitic intent.

(para 24)

Unfortunately, this doesn’t really help. To take the second statement, for example, in what sense can it ever be antisemitic “to hold the Israeli Government to the same standards as other liberal democracies”? What kind of caveat is this? The first caveat is in principle more helpful, a clear recognition that there is a problem with the strictures of the EUMC working definition. But it is contradicted by the Committee’s obvious eagerness to define a broad range of statements as antisemitic when it comes to Israel (para 17 again), giving encouragement to those who think like it, to find antisemitic intent. The presumption throughout, that criticism of Israel is dangerous ground to enter, is if anything strengthened – as, I submit, those who favour the EUMC-now-IHRA definition have always intended. If nothing else, it chills the atmosphere for the serious debate about Israel and Palestine that is so urgently needed. Although it can’t be quantified, anecdotal evidence from a number of Labour party branches suggest that many members now find this whole issue too difficult to discuss. Similarly on a number of university campuses there is pressure not to raise issues around Israel-Palestine on the grounds that these make some students feel “uncomfortable”.

It is clear, however, that the debate about Israel-Palestine won’t go away. If the Home Office Committee had recognised this and tried more carefully to elaborate ways in which it could be developed constructively, it might have contributed to defusing less constructive reactions – particularly on campus – when the realities of Israeli politics are raised. While the occupation continues, while Palestinians within Israel are subject to increasingly discriminatory laws, attempts to understand the reality by employing concepts like “apartheid”, “settler-colonialism” or simply “Israeli racism” are bound to flourish. So too will non-violent campaigns to oppose oppression on the ground by exerting pressure on the Israeli government – and on the British to act more decisively – by means of grass-roots boycott and divestment campaigns and calls for sanctions. Diverting attention back into a recycled version of a tired, politicised definition of antisemitism will not help. By rolling up so much of what is intended as political criticism into what is purportedly antisemitic it is far more likely to debase the currency.

The outlines of a genuinely workable definition of antisemitism is easily to be found, and indeed Chakrabarti should perhaps have ventured here. Professor David Feldman (later co-vice-chair of the Chakrabarti Inquiry) provides a good foundation in his Sub-Report for the Parliamentary Committee against Antisemitism for its investigation into Antisemitism in Public Debate during and after Operation Protective Edge (Jul-Aug 2014). He writes:

Specifically, I propose two distinct but complementary definitions of antisemitism. One definition focuses on discourse, the other focuses on discrimination.

1. When we consider discourse we focus on the ways in which Jews are represented. Here we can say, following the philosopher Brian Klug, that antisemitism is ‘a form of hostility towards Jews as Jews, in which Jews are perceived as something other than what they are.’ Accordingly, antisemitism is to be found in representations of Jews as stereotyped and malign figures. One such stereotype is the notion that Jews constitute a cohesive community, dedicated to the pursuit of its own selfish ends. It will be important to ask whether this or other malign stereotypes figured in public debate on Operation Protective Edge.

2. In addition to antisemitism which arises within the process of representation there is also

antisemitism which stems from social and institutional practices. Discriminatory practices which disadvantage Jews are antisemitic. Taking a historical view, we can say that British society and the British state became less antisemitic in past centuries as Jews were allowed to live in the country, to pray together, to work, to vote and to associate with others in clubs and societies to the same degrees as their Christian fellow-subjects. Discrimination against Jews need not be accompanied by discursive antisemitism, even though in many cases it has been. If we apply this definition of antisemitism to public debate on Jews and Israel last summer and autumn we will need to ask whether any aspect of this debate threatened to discriminate against Jews.

It is a practical definition and operational in its approach. It can easily be reformulated to be independent of and to go beyond its roots around Operation Protective Edge. For reasons still not clear, the Home Affairs Committee sidestepped engaging with it in favour of a reversion to a definition in which criticism of Israel returns as a central feature in talking about antisemitism.

Antisemitism is special

Chakrabarti was very clear that antisemitism had to be investigated in the wider context of racism in general:

[My] clear view is that there is not, and cannot be, any hierarchy of racism. This must stand regardless of perceptions, realities or stereotypes about which racial groups may, or may not, be more established or more or less discriminated against at any given moment. (p.4)

Of course antisemitism has its own specificities but for the Committee’s Report to suggest that the distinct nature of post-Second World War antisemitism (which it claims is unappreciated by Jeremy Corbyn) is that “unlike other forms of racism, antisemitic abuse often paints the victim as a malign and controlling force rather than as an inferior object of derision, making it perfectly possible for an ‘anti-racist campaigner’ to express antisemitic views”. (para 113). What about the accusations of hoarding wealth and goods, deployed against Ugandan Asians in the sixties, that drove so many of them to seek asylum in Britain? What about the Hutu view of Rwandan Tutsis as an exploitative and controlling minority? And as for this being a distinctly post-Second World War trope the Protocols of the Elder of Zion and Nazi antisemitism clearly saw Jews as “a malign and controlling force”.

The Committee goes further: “The Chakrabarti report… is clearly lacking in many areas; particularly in its failure to differentiate explicitly between racism and antisemitism” (para 114).

I have to admit to being one of those who cannot see how (or why) to differentiate explicitly between racism and antisemitism; nor how to oppose one without opposing the other. Or to put it differently, I understand antisemitism as a specific form of racism directed towards Jewish people. Like all racisms it has its own specificities and these need to be clearly taken into account in any strategy to combat this particular form of racism. But equally, as David Rosenberg of the Jewish Socialists’ Group put it in the JSG response to this Report: “There is no separate solution for the problems that Jews face in Britain today. A society that regards Jews positively and treats them properly will be a society that treats all minorities properly.”

It is hard to see what the Committee believes follows from its rigid separation of antisemitism from racism, but coupled with its insistence on trying to define out of court certain criticisms of Israel, this is bound to be counter-productive.

The Israel-Palestine conflict has, for good or ill, become one of the moral touchstones of our age. The British government and indeed the Labour party may well support a two-state solution. But is it credible any longer to maintain that the status quo is provisional and that the Palestinians will soon be exercising their national, political and civil rights in their own state? Not in any future that Israel is currently offering. So the question increasingly posed on campuses, in the Jewish community and elsewhere – in short, wherever this is debated – is whether or not to be complicit in the indefinite denial of fundamental human rights to millions of people? This is a denial of rights being carried out by Israel, with occasional criticism but no effective action to stop it by western democracies. As Tony Klug and Sam Bahour suggested a few years ago, western democracies should stop letting Israel off the hook: “The laws of occupation either apply or do not apply. If it is an occupation, it is beyond time for Israel’s custodianship – supposedly provisional – to be brought to an end. If it is not an occupation, there is no justification for denying equal rights to everyone who is subject to Israeli rule, whether Israeli or Palestinian.”

To repeat the Committee’s words: “Israel is an ally of the UK Government and is generally regarded as a liberal democracy, in which the actions of the Government are openly debated and critiqued by its citizens.” (Conclusions, para 2). It is precisely Israel’s claim to be a defender of liberal democratic values while carrying out its policies of oppression, expansion, suppression of the Palestinians that causes so much offence. Other countries may indeed be far worse oppressors, but which other country at the same time tries to elicit our complicity by claiming to act in defence of our liberal-democratic values? Of course those who take these values seriously are likely to be very critical of Israel. Trying to police the borders of this criticism in the name of fighting antisemitism smacks of a cynical political motivation. It is a poor substitute for dealing with any of the issues, whether it is defending Palestinian human rights or tackling antisemitism at its roots in Britain.

A final note on the style of the report

It’s impossible to read the report without being struck by its all-too-often snide and judgmental tone, its cavalier use of evidence, its cherry-picking of statements made by witnesses to it, its failure to challenge and test the assertions made, and indeed its failure to call or cite witnesses who might have been more challenging of some of the statements made by Rabbi Mirvis and Jonathan Arkush speaking on behalf of an allegedly united Jewish community. The feeling that this reader is left with is that this failure must be because the Report’s authors agree with the opinions expressed. But all too often, that’s all they are. Opinions. Not facts.

Richard Kuper

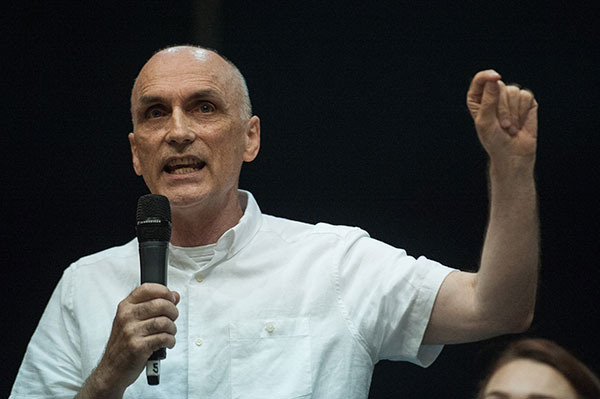

Chris Williamson is an outspoken socialist and supporter of the Corbyn project, so it is no great surprise to find him the subject of a witch hunt. A campaign that has now led to threats of violence to prevent him speaking. Continue reading “The witch hunt against Chris Williamson and WitchHunt”

Chris Williamson is an outspoken socialist and supporter of the Corbyn project, so it is no great surprise to find him the subject of a witch hunt. A campaign that has now led to threats of violence to prevent him speaking. Continue reading “The witch hunt against Chris Williamson and WitchHunt”