Phil Edwards reprinted by permission from his blog, Workers’ Playtime where it was published as the second part of a series ‘Like a Lion’

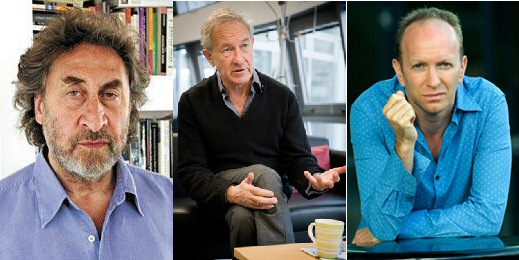

The Jacobson/Schama/Sebag Montefiore letter [paywall] published in The Times on 6 November about anti-Zionism deserves a proper look. The first thing to say is that, while there is an argument there, there’s also an awful lot of confusion and rhetorical inflation. This may just be because Howard Jacobson – who seems to be the lead author – is a muddled thinker and a windy writer, but I think it also has something to do with the subject.

The trouble starts with the first introduction of anti-Zionism:

constructive criticism of Israeli governments has morphed into something closer to antisemitism under the cloak of so-called anti-Zionism

Either anti-Zionism is a genuine position being used opportunistically as a façade – a ‘cloak’ – for antisemitism (cf the Doctors’ Plot), or the name ‘anti-Zionism’ is a polite label for antisemitism (“so-called anti-Zionism”). Can’t be both; you can’t ‘cloak’ antisemitism in antisemitism-with-another-name. What anti-Zionism is, in the authors’ eyes, remains unclear.

demonisation of Zionism itself – the right of the Jewish people to a homeland, and the very existence of a Jewish state

But ‘Zionism’ (itself) isn’t equivalent to what follows the hyphen. In fact they’re three distinct, if related, things – a political ideology (Zionism), that ideology’s core belief (a Jewish homeland) and its concrete institutional expression (the state of Israel). This matters, because it’s possible to hold that core belief while also believing that the existing state of Israel is a monstrosity, or even that the historical development of Zionism has gone badly astray. Not to mention the fact that it’s possible to challenge and oppose Zionism – even to deny that the Jewish people have the right to a homeland – without demonising Zionism.

Accusations of international Jewish conspiracy and control of the media … support false equations of Zionism with colonialism and imperialism, and the promotion of vicious, fictitious parallels with genocide and Nazism

Despite its phrasing, this is three separate charges, not one – and they’re not all equally strong. Yes, the racist myths of a ‘Jewish conspiracy’ live on – there are still people wibbling on about the Rothschilds and (God help us) the Protocols, some of whom believe themselves to be on the Left. Those myths, and those people, need to be challenged; this, though, doesn’t give a free pass to the actual lobbying efforts which are carried out by the Israeli state and its allies, some of which – like most lobbying – go under the radar. (Anyone still maintaining that all talk of a “Zionist lobby” is Protocols-level antisemitism will have to explain who the Conservative Friends of Israel are and what they hope to achieve.)

I’m less sure about false equations of Zionism with colonialism and imperialism. Zionism was conceived as a colonialist project, to be implemented by arrangement with the great powers of the day. Here’s Theodor Herzl, writing in 1896:

Should the Powers declare themselves willing to admit our sovereignty over a neutral piece of land, then the Society [of Jews] will enter into negotiations for the possession of this land. Here two territories come under consideration, Palestine and Argentine[sic]. … The Society of Jews will treat with the present masters of the land, putting itself under the protectorate of the European Powers … If His Majesty the Sultan [Abdul Hamid II] were to give us Palestine, we could in return undertake to regulate the whole finances of Turkey. We should there form a portion of a rampart of Europe against Asia, an outpost of civilization as opposed to barbarism. We should as a neutral State remain in contact with all Europe, which would have to guarantee our existence.

Imperialist carve up

In the event the Ottoman Empire[sic] didn’t survive World War I. Its spoils were divvied up between the French and British empires[also sic]; the latter, anticipating that it would have control of Palestine when the music stopped, declared in 1917 that His Majesty’s Government

view[ed] with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and [would] use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country

(Shame about that ‘clear understanding’; really should have got it in writing.)

In any case, from 1896 to 1948 Zionism was, precisely, a colonialist project to be carried out on land held by imperialists. Even after 1948 – and especially after 1967 – Zionism continued to be a colonialist project, inasmuch as it was carried forward by the continual establishments of ‘settlements’ on land held by force. The idea that equating Zionism with ‘colonialism and imperialism’ is a slur – let alone that it’s straightforwardly ‘false’ – is quite bizarre; it’s a very surprising proposition for two historians to put their names to. I can only imagine that the underlying logic here is something like the Forward article which attempted to rehabilitate Christopher Columbus from charges that he “brought nothing but misfortune and suffering to the indigenous Americans”, by likening him to Herzl as “a visionary looking for a safe home for the Jewish people”. There’s colonialism and then there’s colonialism in a good cause – quite different.

The Holocaust is singular

As for the third point on the list – vicious, fictitious parallels with genocide and Nazism – again, we need to be careful (a great deal more careful than the writers of the letter were, frankly). What are “vicious, fictitious parallels”? The argument seems to be that parallels between Israel and the Nazis can only be sustained by falsifying the evidence, and are only advanced with the intention of causing offence. I think this is mostly – but not entirely – unsustainable. Drawing an analogy between two things isn’t saying that they’re the same: to say that X is like Y in certain ways is also to say that it’s unlike Y in other ways. So, for instance, there’s a parallel between the Nazis setting up internment camps for political enemies in 1933 and the British interning their political enemies in South Africa (1900) and Northern Ireland (1971); there are also lots of differences between those situations. Still, interning people without due process is something the Nazis did, and that parallel may give us a reason to think twice about our own government doing it. Were the Israeli government’s actions in putting Gaza “on a diet” comparable to the Nazis’ starvation of the Polish ghettoes? There does seem to be a point of similarity; you may think that similarity is outweighed by so many dissimilarities as to be irrelevant, but I don’t think it can be ruled out of court.

The big dissimilarity, of course, is the Holocaust, which may be held to override and delegitimate any smaller parallels. In particular, if you hold the view (advanced by historians such as Lucy Dawidowicz) that the Nazis came to power already intent on the extermination of the Jews, then it’s clear that the Nazi regime was out on its own in the genocidal evil stakes, and almost no other government can be compared to it – not Stalin’s, not Mao’s, not the British in India and certainly not Israel. (I say ‘almost’ – there’s some evidence that the Khmer Rouge were planning genocide from the start.) But even this isn’t as solid a distinction as we might want it to be. The ‘functionalist’ school of historians – people like Christopher Browning – dispute the ‘intentionalism’ of Dawidowicz and others: the ‘functionalists’ argue that the Nazis came to power wanting to rule a Europe with no Jews, and that the Holocaust as we now know it developed out of a whole series of short-term expedients to bring this about. The Nazis on this reading were certainly never humanitarians – at best they were indifferent to whether Jews lived or died – but genocide was the means, not the end. What they wanted, at least from 1939 (arguably from 1933), was land, only without some of the people who lived on it. This reading clearly makes parallels with other regimes more available, and more troubling.

Of course, drawing any analogy between Israel and the Nazis is grossly offensive to Jews who support Israel – which is to say, the great majority of Jews – and for that reason I think non-Jews should avoid doing so; I’d even go so far as to say that for a non-Jew to publicly and deliberately use this parallel, despite the offence it is bound to cause, suggests an indifference to Jewish feelings which verges on antisemitism. That said, the offensiveness of the parallel isn’t news to anyone; in fact, it’s precisely why people use it – Jewish people very much included. My experience of arguments about Zionism conducted mostly among Jews is that Godwin’s Law is in full effect, in a fairly fast-acting form; Nazi parallels are freely thrown around on all sides, including sides that non-Jews might not even know about. (Amos Oz, in In the land of Israel, recalls seeing graffiti in an Orthodox area of Jerusalem likening the Labour Mayor to Hitler – Teddy Kollek, that is, not Ken Livingstone.) Invading and occupying land illegally? Just like a Nazi! Threatening the security of Israel and the survival of the Jewish people? Just what the Nazis wanted! Betraying the Jewish faith itself by worshipping the goyim naches of a nation-state? No better than the Nazis! And so on, to the point where it’s quite hard to believe that anyone involved is hearing this stuff for the first time, or taking genuine offence – least of all, incidentally, when the offensive conduct complained of seems to consist of quoting Himmler on the topic of Nazi racial policy. But this is of its nature an argument within the Jewish community. Speaking as a non-Jew, I’m happy to forswear comparisons between Israel and the Nazis myself, and leave them to it.

Back to Jacobson and friends:

Zionism — the longing of a dispersed people to return home — has been a constant, cherished part of Jewish life since AD70.

The Jews have always been Zionist. Who knew?

In its modern form Zionism was a response to the centuries of persecution, expulsions and mass murder in Christian and Muslim worlds

Oh, wait. What we now call Zionism is the modern form of Zionism. So they’ve always been Zionist, only in different ways – and specifically not in the way that we know. So earlier forms of ‘Zionism’ weren’t actually what we now call Zionism. Only they were Zionism, because… um.

[Zionism’s] revival was an assertion of the right to exist in the face of cruelty unique in history.

Or was it that the Jews used to be Zionist, and then they weren’t, but now they are again?

Zionism is more than the dream of ‘return’

As you can see, the confusion level ramps up at just the point where the argument becomes most tendentious. Certainly the idea of a Return – the idea of Zion – has been part of Jewish life since the destruction of the Temple, if not the Babylonian Captivity; but that’s very different from saying that Zionism has been. Zionism translated the idea of Zion into the language of political nationalism, and aimed to implement it (as we’ve seen) under the auspices of European imperialism; it couldn’t reasonably have arisen before the early nineteenth century, and in any case historically didn’t arise before the 1890s.

It’s also worth noting that, while Zionism certainly did flourish as a response to organised antisemitism, it was far from being the only response. While Dawidowicz’s own sympathies were with Zionism, her superb book The War Against the Jews shows very clearly that Zionists were a minority in occupied Poland (the European country with the largest Jewish population before the Holocaust and the greatest losses as a result of it, approaching three million). To be more precise, Dawidowicz’s account suggests that there were three main organised groups within the Polish Jewish community: Zionists, Orthodox Jews and the socialist Bund, which called for Jews to organise as Jews within their own nations. The Bund – which by this stage only existed in Poland – was all but wiped out by the Holocaust; this led to the tragic irony of its effective erasure from history, enabling contemporary Zionists to present their own political forebears as the authentic voice of the Jewish people.

We hope that a Palestinian state will exist peacefully alongside Israel. We do not attempt to minimalise[sic] their suffering nor the part played by the creation of the state of Israel.

As Robert Cohen points out, this is mealy-mouthed in the extreme. It’s not so much that Palestinian ‘suffering’ was exacerbated by the creation of the state of Israel, more that it was its direct and inevitable consequence. “How could the project of Jewish national return with Jewish majority control of the land ever have been achieved without the displacement of the majority people already living there? … the 1948 Nakba was Zionism in action”. A supporter of present-day Israel expressing sympathy for Palestinian suffering can’t help looking a bit like the Walrus weeping for the oysters.

Yet justice for one nation does not make justice for the other inherently wicked.

Indeed, and quite the contrary – justice for one is justice for all; justice for the people of Palestine must necessarily mean justice for the people of Israel. Similarly, justice for the poor can only come through justice for the rich. To say that you’ve had justice doesn’t necessarily mean that you’ve received – or kept – what you wanted, though. But this doesn’t seem to be the idea of justice that the authors have in mind. Rather, the suggestion seems to be that people who have repeatedly seen their land confiscated, their leaders assassinated, their towns demolished and their children imprisoned nevertheless still owe something to the state that’s done all this, and that it’s only fair to keep them waiting for justice until they’ve delivered it. Again, it’s hard to identify with this position. If ‘position’ is the word.