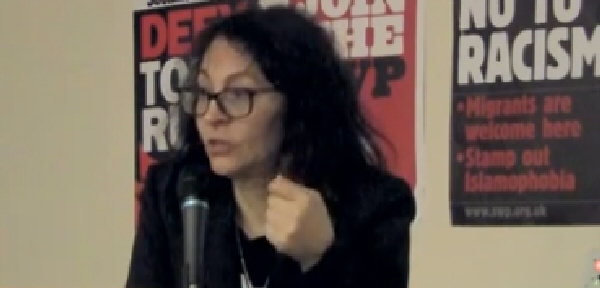

Karma Nabulsi writes about Prevent

[Editor’s note. These are extracts from Don’t Go to the Doctor by Karma Nabulsi published in the London Review of Books and reprinted by permission. We are republishing it not just because of its intrinsic interest but because of the link between the IHRA definition of antisemitism and the Prevent programme. We are finding that allegations of IHRA antisemitism, no matter how wild and unfounded, are producing referrals to the Prevent programme; these referrals are being used as a pretext to raise concerns of threats to public order or campus security and justification for cancellation of the event. In this way spurious claims of antisemitism are effective in halting discussion of Israel without any scrutiny of the validity of the allegations. A link is being made between unacceptable and deplorable acts of violence and free expression of of areas of legitimate public concern. The war on ‘terror’ segues into a war on free speech. Mike Cushman]

A colleague of mine at Oxford was asked to see an undergraduate who was falling behind in her work. The student – a Muslim – explained that she had been suffering from depression and was being treated for it by her GP. My colleague believed the student’s explanation placed her under an obligation to ask the student whether she was being radicalised.

….

A librarian was asked for a reference by another university: ‘Are you completely satisfied,’ they wanted to know, ‘that the applicant is not involved in “extremism” (being vocal or active opposition to fundamental British values, including democracy, the rule of law, individual liberty and mutual respect and tolerance of different faiths and beliefs)?’

Out of the blue, a college head refused the usual joint arrangements with a university centre for a lecture by a very distinguished European academic, whose work is on the politics of Islam. Special Branch had informed the college that a great deal of extra security would be required.

….

A student society set up decades ago to represent a well-established immigrant community in the UK wanted to hold welcome drinks for new undergraduates at the beginning of the academic year. The university told them to hand over the guest list 48 hours before the event. They explained that they had no way of knowing who would turn up, as the event was to welcome new members, but offered to check university IDs at the door, take names, or have a senior member in attendance – no, they couldn’t hold the event, it was against the new rules. One of the organisers was sent an explanatory email: ‘The event was impossible without a guest list because of our legal duty to abide by Prevent. All colleges across the university must screen guest lists before they offer an event, for security purposes … our hands are simply tied on this one.’

The British government’s Prevent programme, aimed at keeping people from being ‘drawn into terrorism’, was developed in 2003, after the invasion of Iraq, as part of the overarching counter-terrorism strategy known as Contest. Revised in 2008, 2011 and 2015, it consists of four ‘workstreams’: ‘Pursue: to stop terrorist attacks; Prevent: to stop people becoming terrorists or supporting terrorism; Protect: to strengthen protection against a terrorist attack; and Prepare: to mitigate the impact of a terrorist attack.’

How Prevent operates

Under the 2015 Counter-Terrorism and Security Act, the latest incarnation of the Prevent programme imposes a legal duty on public bodies, and the people who work for them, to spot the early warning signs of terrorist sympathy in individuals, and report them. There is ‘statutory guidance’ explaining what the signs could be. ‘Non-violent extremism’, said to be the gateway to ‘violent extremism’ and part of the ‘radicalisation process’, is defined as ‘vocal or active opposition to fundamental British values, including democracy, the rule of law, individual liberty, and mutual respect and tolerance of different faiths and beliefs. We also include in our definition of extremism calls for the death of members of our armed forces.’ According to the government’s counter-terrorism strategy, ‘extremist’ ideology is the core problem, and terrorism its outcome, even though substantial research on radicalisation and extremism suggests that a complex mix of social, psychological, political and strategic factors all have a role to play. Louise Richardson, Oxford’s vice-chancellor and an expert on terrorism, has publicly described the Prevent strategy as ‘wrong-headed’ – but the university is still legally bound to spend time hunting for proto-terrorists.

Prevent relies on two analogies to explain how individuals are drawn into ‘non-violent extremism’ and then ‘radicalised’ into terrorists. The first is the conveyor belt, or escalator hypothesis. Prevent aims to identify and catch people before they step onto the conveyor belt that will carry them from thinking bad thoughts to doing bad things – in other words, not only before any crime is committed, but before it is even dreamed up. The second is the iceberg hypothesis, first floated by Colonel Chuck Cardinal, the director of the US Army Pacific Command’s inter-agency co-ordination group for counter-terrorism, who suggested that ‘Islamic extremists’ are like icebergs, floating, and mostly submerged, in a sea of ‘moderate Muslims’. So how are we supposed to spot them?

There is no comprehensive list of possible indicators that someone is ‘vulnerable to terrorism’, but the government has come up with a partial list in the official guidance that accompanies the primary legislation:

Identity Crisis – Distance from cultural/ religious heritage and uncomfortable with their place in the society around them.

Personal Crisis – Family tensions; sense of isolation; adolescence; low self-esteem; disassociating from existing friendship group and becoming involved with a new and different group of friends; searching for answers to questions about identity, faith and belonging.

Personal Circumstances – Migration; local community tensions; events affecting country or region of origin; alienation from UK values; having a sense of grievance that is triggered by personal experience of racism or discrimination or aspects of government policy.

Unmet Aspirations – Perceptions of injustice; feeling of failure; rejection of civic life.

Criminality – Experiences of imprisonment; poor resettlement/reintegration; previous involvement with criminal groups.

‘However,’ it goes on, ‘this list is not exhaustive.’

If you are identified as ‘vulnerable to being drawn into terrorism’, you are reported – or ‘referred’ – to the police. Referrals can come from teachers, council workers, social workers, doctors, university lecturers, nurses, librarians or opticians. Thousands of mostly Muslim men and boys, along with a few right-wing extremists, have been flagged ‘at risk’, and sent on courses under the so-called Channel programme. It is ‘voluntary’, and offers a range of social and psychological processes intended to deradicalise young British Muslims.

The latest figures, obtained via a Freedom of Information request to the National Police Chiefs’ Council, show a sharp jump in referrals to Channel after the 2015 Act. Sixty children are referred to Prevent every week. In the year to June 2016, there were 2311 referrals of under-18s – an increase of 83 per cent on the previous year – of whom 352 were aged nine or under. Referrals from schools climbed to 1121 from 537 the previous year. In a report for the Institute of Race Relations, Frances Webber wrote that ‘the context for Prevent’ is an ‘increase in racist violence and extremely negative stereotypes of Muslims … Islamophobia and far right extremism have become more mainstream, with nearly one third of young children believing Muslims are taking over England and over a quarter believing that Islam encourages terrorism.’

One NGO website asks parents if their children have ‘become overly passionate in some of their viewpoints’ or ‘refuse to listen to those who don’t share their views’. But parents are often not told that their children are being investigated. Some are only told about the investigation after it ends, and many are suspects themselves. Last year a friend told me about a Syrian refugee family recently arrived in his town. He and his wife, who had met them at the mosque, helped them to settle in. At nursery, their son (who spoke almost no English) was constantly drawing pictures of planes dropping bombs. Rather than ensure the child received help to get over his traumatic experiences, the nursery staff called the police. The parents were visited by the local force, separated and questioned: ‘How many times a day do you pray? Do you support President Assad? Who do you support? What side are you on?’ The police just shouted louder when the parents didn’t answer immediately (they didn’t always understand what they were being asked).

The application of the legislation is cumbersome and detailed. Prison officers, childcare workers, staff in hospitals, doctors’ surgeries, welfare services and town councils, higher education administrators and teachers are now deeply immersed in the daily chores necessary to demonstrate compliance with ‘the Prevent duty’. We have to fill out ‘risk assessment’ templates that chart the measures to be taken. There are also lengthy ‘action’ templates, to demonstrate progress at each stage, with ‘benchmarks’, training manuals, guides and slides, workshops, seminars and online courses, accompanied by conflicting and copious literature, official and unofficial guidance, published at regular intervals, with updates, new suggestions and more forms – all of which come attached with dark warnings of the trouble ahead if you don’t (or won’t) fill in the forms or carry out the suggested activities.

Non-compliance carries the risk of your institution losing its funding. The authorities require material proof that you have been on your guard throughout the year. There are spaces on the action templates where you have to demonstrate, in writing, exactly how you (and everyone you line-manage) have been looking out for extremist behaviour and views. You must offer concrete examples of how and when you have done this.

….

Even on its own terms, Prevent is a failure, as well as being counterproductive. In early 2011, the Equality and Human Rights Commission reported that not only do the measures in many cases breach human rights law, but ‘counter-terrorism laws and policies are increasingly alienating Muslims, especially young people and students,’ and ‘counter-terrorism measures may themselves feed and sustain terrorism.’ MI5 rejected the conveyor belt theory in 2008, in a report leaked to the Guardian. In 2010, the incoming coalition cabinet received a briefing (leaked to the Sunday Telegraph) that warned them not ‘to regard radicalisation in this country as a linear “conveyor belt”, moving from grievance, through radicalisation, to violence

….